|

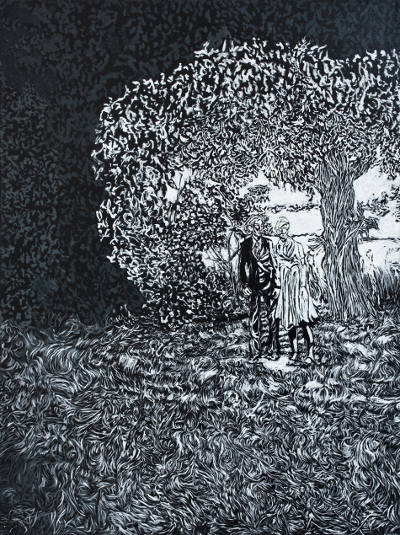

| Viktor Rosdahl, The Wedding, 2013, image: Christian Larsen |

In “Ytterstad / Outskirts” Viktor Rosdahl includes more human figures and visages than in previous exhibitions and employs a tone which seems more reverent than before.

When one releases themselves from the burden of their ego and instead adopts an alternate position, tangents and rhizomic formations tend to breed new combinations for creation. When an artist pushes its viewer to examine a painting from two distinct perspectives, frontal view and backside, how should one consider such a work? Is each side to be taken into account separately or simultaneously? Should one move between views to encompass both the singular and compounded experience of both visual stimuli? Critic Magnus Bons remarks that this method of painting on both sides has appeared before in history and, as example, gives a two-sided painting taken out of context by Hieronymus Bosch at Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, illustrating an estranged Christ carrying the cross amidst the masses on one side versus a naked child holding a pinwheel on the other. Viktor Rosdahl uses this same double-sided method in Stuyvesant / Cooper Village (2013), where one sees from the front a black-and-white cityscape stylistically compatible with the others in his oeuvre; the backside shares a geometric skyline with his signature factory smoke swirls in pastel hues.

This exhibition incorporates human figures and visages more so than previous exhibitions viewed at both Christian Larsen and elsewhere which have included Rosdahl’s work—exhibitions which focused more on the absence of humanity and human form and more on gothic cityscapes, sweeping architecture, maelstroms and stark, industrial scenes. Instances of flesh surface in “Ytterstad / Outskirts” where one is meant to regard the presence of humans—even if such humans appear as ill, remote characters suffering an unfortunate scene. In The Wedding (2013), an askew couple is centrally positioned yet alone in a lush, foreboding forest; in Nattkvarter-Selma (2013), the visage of a young girl is partially covered by her own hair—her mouth agape. The child can be seen through a ripped hole into another seemingly intimate realm. This peephole mode has been used by Rosdahl in other works such as Hole in the Wall (2004-2005).

Previous shows such as Gävle Konstcentrum’s “If the Light Should Take Us” illuminated Rosdahl at the height of his extremes, with pieces such as The Need to See You Dead (R.I.P. Jussi Hirvilammi) (2008) emphasizing his talent for intricate panoramas in addition to the artist’s unconventional usage of materials like stretched plastic-as-canvas in Dark Throne (2010) or stolen tarpaulin in Amaltea Dreams (2007). This exhibition clearly allows one to view immediate results of a laborious artistic method. Whilst other artists might choose to adopt a more conceptual route in response to our era, focusing on some ‘potentiality’ or ‘future’ of x, y or z, this can be exhausting and even perceived as cowardice. But where is the art? And what does it mean? The public may find themselves at a loss as they wander from room to room in parallel exhibition spaces, perhaps, left to conclude that any given contemporary artist’s tricks (e.g. appropriation, highlighting the unfinished, unrealized or inconclusive, jumping onto a trend-driven, idealogical wagon of their choice) cannot match the weight of an artist’s unavoidable hard work, sheer will and graceful design in action. Before the art world takes another step closer towards dissolving or overriding concurrent modes of work and production, one should consider works such as Rosdahl’s which would devalue or even possibly disappear with such a loose gesture.

If one considers each artist in the midst of a series of spoken or unspoken conversations with their audience, then Rosdahl’s conversation has slightly veered from its previous trajectory of magnified chaos and despair, instead aiming for a tone which now seems more reverent, questioning how each world and/or sub-world may indeed be intertwined—for better or worse. Where once the absence or aftermath of humanity prevailed, one now detects visceral remainders, whether isolated or otherwise, creeping into view with increased frequency.

To see the review in context, click here.