|

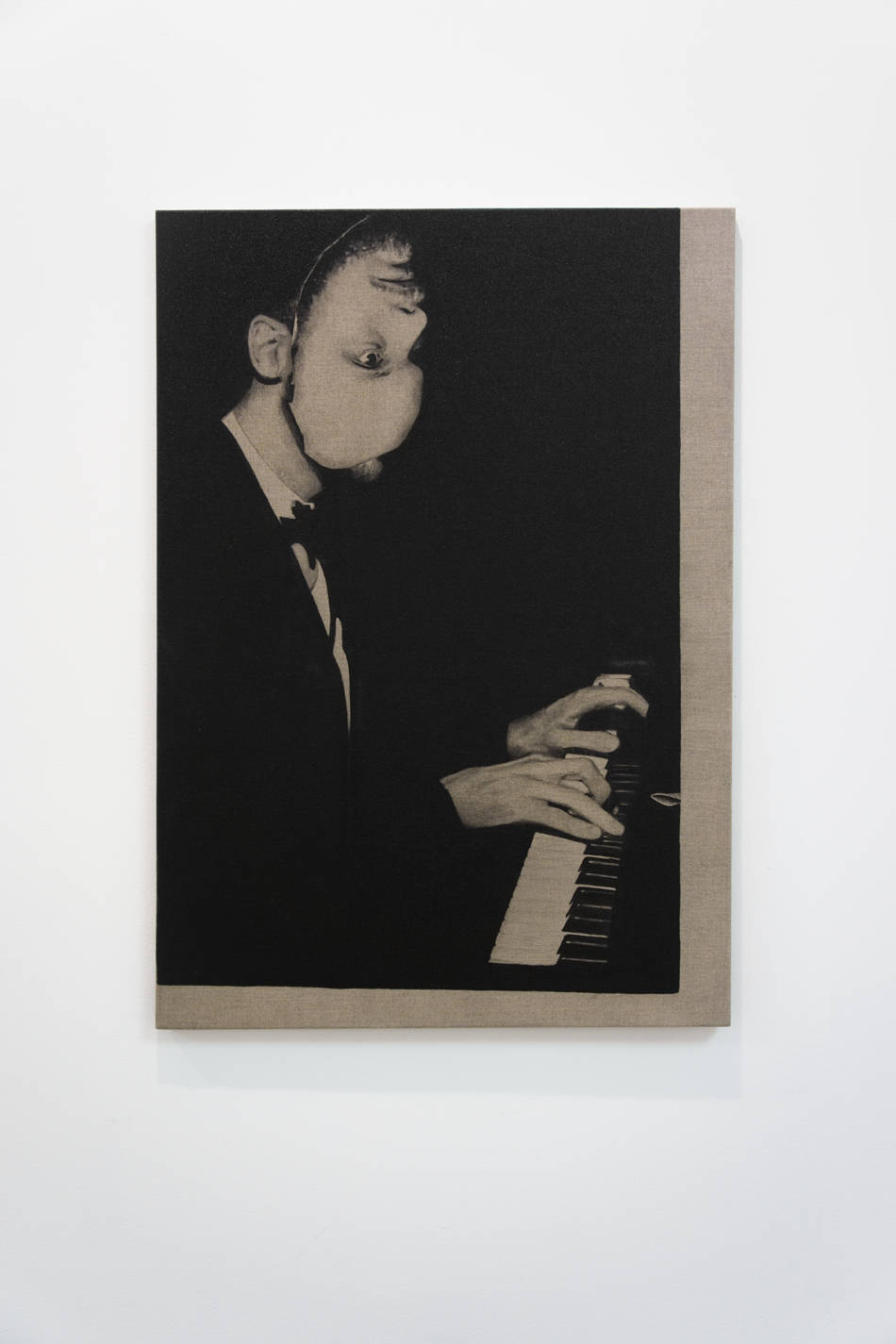

| Carl Johan Högberg, JJ, 2012, image: Christian Larsen |

Carl Johan Högberg’s paintings seem to scan life’s panorama in a manner that suggests, at once, omnipotence and a sense of the absurd. Influenced by the Surrealists and rooted in photomontage, the Amsterdam-based Swedish artist’s work grapples with what lies underneath the obvious or the unthinkingly accepted – so that what first seems a display of playful creations, featuring youthful individuals in the midst of casual leisure, overt exhibitionism or theatrics, harbours conscious undercurrents of the grotesque, the delusional and the shameful. Rooting many of these paintings in Max Ernst’s collage Health through Sports (1920), which anticipates the cult of physical fitness that would be warped by the Nazis, Högberg takes ample time to highlight the glorious ambitions and strengths of the human being, even if these same aspirations are manipulated, leading the masses to take a wrong turn or have their intuitive judgment clouded. Högberg’s work pushes one to both sympathise with and pity humanity; sentiments can veer in either direction. Viewing the work may reinforce misanthropic feelings, or it might cajole one to shed discontent with how flawed existence can be and move towards a more enlightened tomorrow.

The complexity of Högberg’s work lies in his decision to embrace and question paradox; a suggested reference to a weighted, historical figure or wildly problematic era is not easily ascertained without noting the title of each work – the faces are not generically famous enough to identify and references are subtle. For instance, the face of Per Albin Hansson, mid-twentieth-century Swedish prime minister and chairman of the Social Democrats, is partially covered by a tropical Monstera leaf – yet most observers would not identify him even if it weren’t there, as memories of this political figure are increasingly lost to history. Elsewhere, in JJ (2012), the visage of legendary Swedish jazz pianist Jan Johansson is defamiliarised by being cut out and rotated upside down, a stumbling block to the viewer recognising him – and his historical significance. (It’s perhaps not irrelevant that Johansson once made a record, under a pseudonym, designed to be exercised to.) The ability and tragic inability to trust what is given or suggested are key elements in this exhibition.

Maintaining a collage aesthetic that initially seems benign, often sporting pastel tones and subjects (fruit, plants, patterning, attractive bodies) which sooth the senses, this collection of works might at first appear intended to do nothing more than placate. Yet upon closer examination this calming effect hints at every individual’s occasional, narcotised inability to differentiate between opposing spheres of acceptable and unacceptable: of ’good’ and ’evil,’ even if such definitions can be mutually agreed upon. But when do an artist’s references prove to be uncouth or inappropriate? To illustrate shattered, defunct ideals of the human being remains unpleasant; yet individuals continue to make horrible mistakes, and some of them never intend or care to learn from errors. These images are eerie and uncomfortable, especially when one becomes aware that each reference is calculated, drawing attention to the allure of now-broken political ideologies and dogmatisms – for instance, Högberg’s images, such as the male nude intersecting with a colour wheel, Untitled (2013), of healthy, attractive individuals in the midst of physical exercise or of sirenlike physiques posing in a manner that Leni Riefenstahl would have approved. Such images, again, reflect the Third Reich’s obsession with wellness, bodily perfection and Aryan genetics: a historical mindset which, one remembers, was unfortunately, though to a lesser degree, also exalted in Scandinavia.To see the review in context, click here.