|

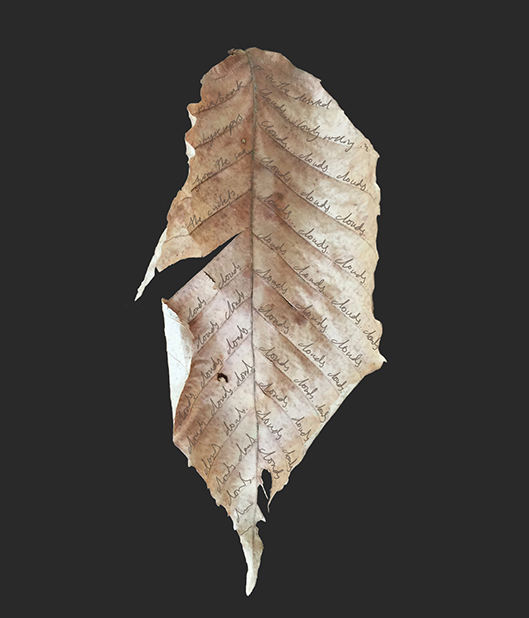

| Fredrik Söderberg, Mandragora, 2009, watercolor on paper, 28 x 38, with frame: 53 x 43 cm, image: Milliken Gallery |

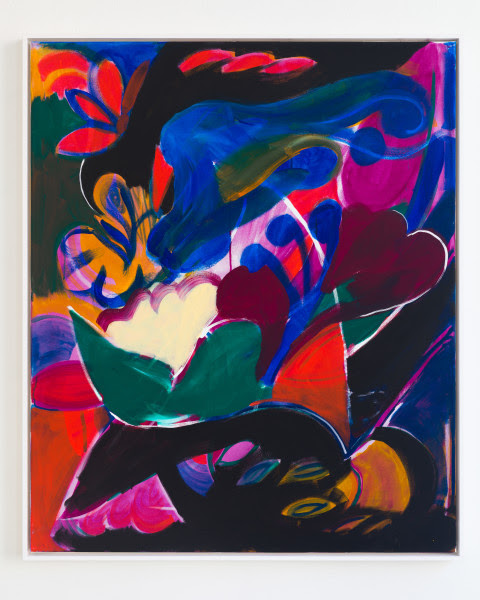

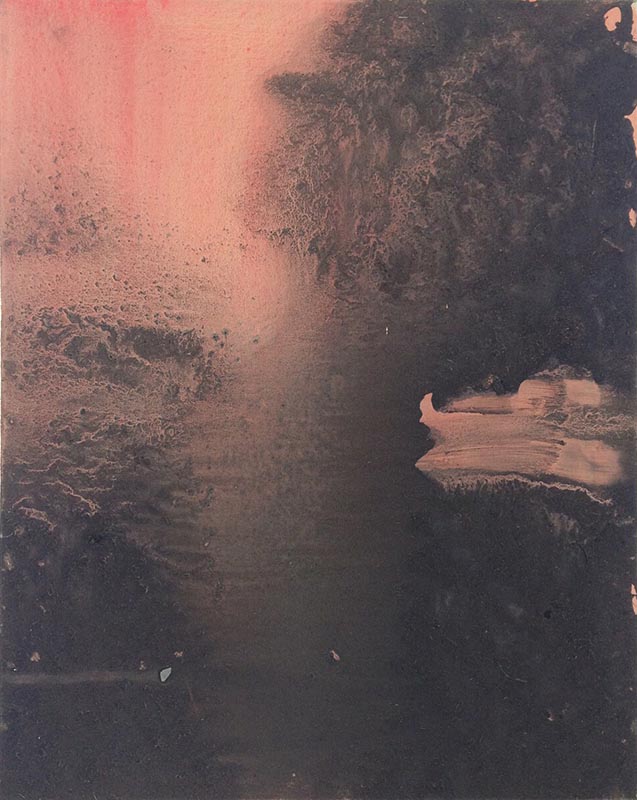

This striking collection of Fredrik Söderberg’s watercolour paintings, entitled ‘We Pray to the Sun and Hail the Moon’, may inspire engaged viewers to question their relationship with infinity and perhaps even dissuade some from swallowing the world’s investment with spiritual redemption or continuing to embrace a detached narcissism. Söderberg’s charm lies in his explorative mapping of self-reflective spiritualisms, as well as in his ability to create provocative microcosms inspired by our own spheres—even if his works may appear cryptic to some.Linked to the transcendental teachings of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn and Aleister Crowley’s philosophies on ceremonial magic and the occult, these unearthed energies are a fresh discovery for those who find themselves removed from any form of spiritualism. Much like Crowley’s wide array of eclectic interests, Söderberg’s paintings investigate the unknown from diverse angles. At first glance, rich watercolours such as Avebury (2009) appear to be timeless landscapes when they are actually secular perspectives focused on the geographies of meditation and transformation. Others, such as Summer Solstice (2008) and The Beginning of Magick II (2008), are extreme in their quest to enlighten the viewer about the pervasive foundation fuelling the occult. These paintings visually interpret hierarchical connections between energy and power through balanced geometries and the recurring presence of cosmic forces—a massive sun or seductive moon—reminding one of a secret Masonic history or ancient Egyptian influences.

Some of Söderberg’s paintings appear to be more preoccupied with a mysterious means to a justifiable spirituality rather than any specific end. In Mandragora (2009), the artist painted a solitary mandrake root suspended, presented as an object worthy of further examination. For the mandrake root is directly associated with occult practices, facilitating rituals and harbouring mythologies related to its own hallucinogenic powers and aphrodisiacal abilities. In Ritual II (2009), time has stopped and the moment of the sacrificial act—whether it is sinister or harmless—becomes the true focal point. Viewers may find themselves questioning the border between psychosexual effrontery and pre-emptive violence.

Such explorations into the occult remain appealing because this cosmic voyage, in part, embodies and preserves the core existential concepts of modern works such as Albert Camus’ The Rebel (1956), in which he writes, ‘But from the moment when a movement of rebellion begins, suffering is seen as a collective experience. Therefore the first progressive step for a mind overwhelmed by the strangeness of things is to realize that this feeling of strangeness is shared with all men and that human reality, in its entirety, suffers from the distance which separates it from the rest of the universe … I rebel—therefore we exist.’ Söderberg cultivates this singular feeling of strangeness that we collectively experience as human beings. Placing emphasis on cultural faux-pas and exception, ‘We Pray to the Sun and Hail the Moon’ exhibits the contradictory influences of cultural artefacts versus the fantastic—but not as they were meant to be initially consumed. Herein lies the beauty of representation. The freedom to rebel is often followed by delightful confusion; Söderberg has managed to instigate both aforementioned sentiments, clearing a trail for the unpredictable. ‘He makes solemn claims for his art spawning alternative experiences,’ comments Ronald Jones in an accompanying exhibition essay, ‘especially where the mysteries of life are concerned. In this sense Söderberg’s art discovers new spiritual vistas, while being earnest, proactive, pre-scientific, and post-critical. His art is allergic to irony.’ Perhaps there is hope for the diligent and searching after all.To see the review in context, click here.