|

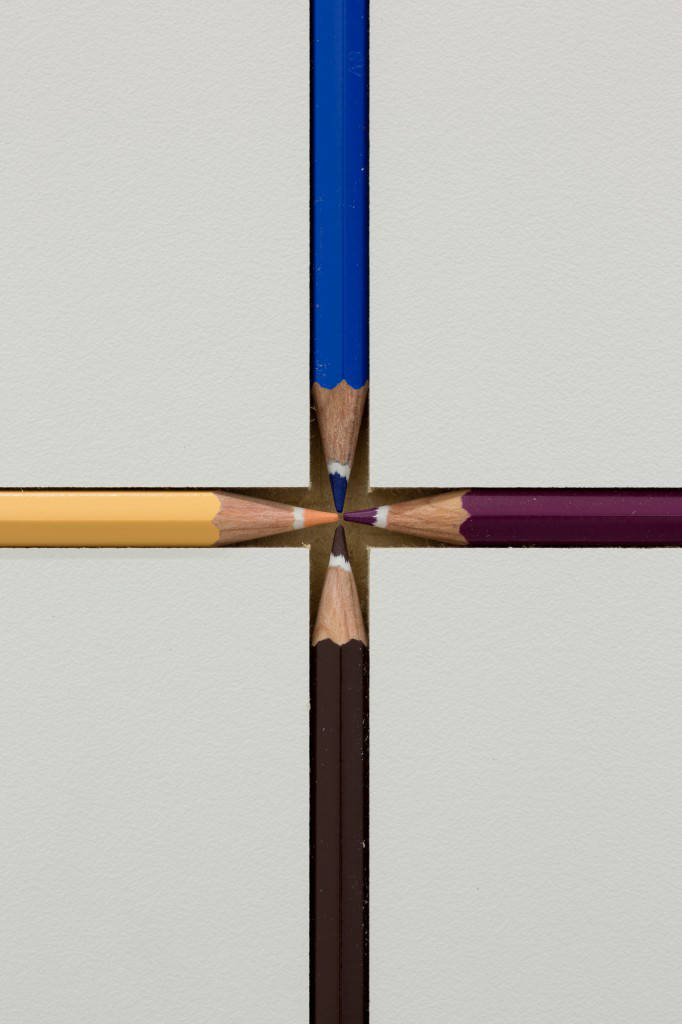

| Jacob Dahlgren, Work as Method, 2013. Image: Andréhn-Schiptjenko. |

Given his history of transforming everyday objects into large-scale installations and intricate constructions that hint at the power of excess and the void, it’s clear that Swedish artist Jacob Dahlgren is no stranger to repetition.

His artistry illuminates both his personal obsession and a commitment to following one path, one notion of simplicity or self-elevated design until its completion. In so doing, Dahlgren emphasises that less is more – that Minimalism still possesses a visual impact on viewers, moulding the mindsets of the masses. Embracing the linear, abstract and geometric, and the human desire to locate order and beauty in a world that often provides neither, Dahlgren’s solo exhibition – his second here – features works (many site-specific or performative) that express how an artist can cultivate awe-inspiring impressions stemming from deliberation and recurring tasks, and from the alteration of domestic objects and common items such as weighing scales, coloured pencils and darts.

Here there appears to be a shift in focus from primarily highlighting Dahlgren’s personal relationship with chosen patterns, stripes or solo-focused work methods, begun nearly a decade ago in works such as Colour Reading and Contexture (2005), towards including everyday citizens in works such as in December 5 Demonstration (2007) (alongside complementary demonstrations occurring in multiple locations worldwide), where strangers walk streets holding his uniquely designed banners and placards (a protest inevitably universalised and anonymised by this motion, for their iconography has no recognisable association) or No Conflict, No Irony: I Love the Whole World (2013).

Here, a colourfully designed 100-metre-long banner, text-free and patterned with coloured lines and shapes, was constructed by the public and sports enthusiasts and carried through Edinburgh, from Meadowbank Sports Centre to Salisbury Crags. This tendency to utilize banners, placards and flags quickly steers one into the realm of politics, asking one to take a closer look at societal constructs, cultural conventions and normative behaviour. In such cases, the artist creates variants of tools like abstract, geometrically designed placards, subverting any tendency to represent real-world ideologies that might be perceived as problematic, vacant or ineffectual.

Oftentimes, Dahlgren’s stripes are incorporated into military and service-oriented uniforms; this visual trademark has been present since his earliest investigations. Yet his relationship with the stripe evolves. Firstly, he obsessively collects and wears striped T-shirts. The film Neoconcrete Space (2012) features 1,027 striped T-shirts that he has worn and will continue to wear until death; in the film Non Object (2013), the artist clandestinely stalks strangers coincidentally wearing similar striped shirts; in Work as Method (2013), stripes are displayed via manipulated coloured pencils placed side by side: parallel, perpendicular, intersecting. In his performance piece and abstract ‘painting’ Neoconcrete Ballad (2013), Dahlgren creates rules for others to collectively create a new piece; they drill holes into the gallery wall, then later place coloured plugs into each hole; the spectator is only able to view the holes, never the individuals working or making the hole; they’re hidden behind a wall as they work.

This gesture persuades one to consider their relationship with work and production, for when a consumer is removed from production, it is easier to objectify the worker and the product. The artist’s choice to highlight the division between spectator and worker mimics the stifled rapport between producer and consumer, so that this performance serves as commentary on how patterns currently present in daily life can be harmful. Yet Dahlgren’s works remain playful even when they have community-based participation in mind.

To see the review in context, click here.