|

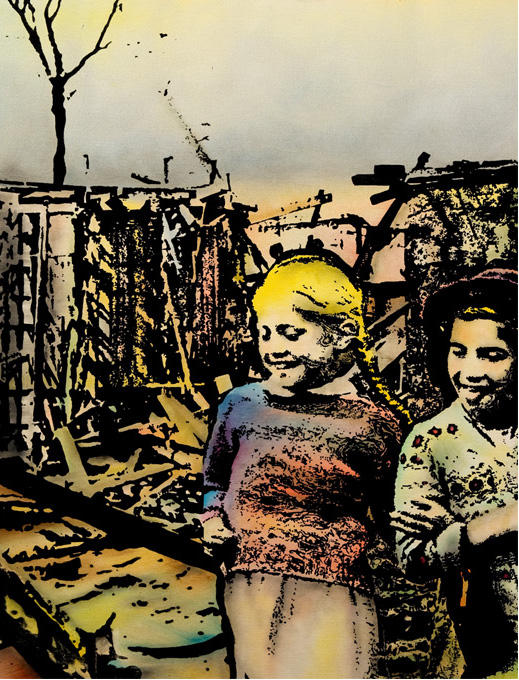

| Christian Saldert, The Politics of the Unpolitical, 2011, image: Christian Saldert |

Only a little by way of explanation is provided about the artist Christian Saldert on his site or on Galleri Kleerup’s site representing him or his recent digital-poetic solo exhibition “Bodies of the Unreal” inspired by found, appropriated web images of American nudists from the mid-twentieth century. Influenced by pop art and an avant-garde collage aesthetic, Saldert’s work stands alone in their own Scandinavian terrain of beauty—mysterious, detached from a world known to most: a suggested “unreal” one, or as a press release remarks, Saldert creates a discussion “about the World Wide Web and our era, about our persona on the Internet and the pretense of being someone you are not.”

Often using large-scale dimensions, the artist’s subject matter adds emphasis to an underrated anonymous or hush-hush view (works such as Funeral Parlour, 2009, are sexually charged, sacrificial, sadomasochistic), and select titles such as To Hell with Culture, 2011, and The Hierarchy of Knowledge, 2009, hint at a rejection of entrenched authority and powers that dictate those who may discover themselves privy—even victim. They are a reminder that ”Golden Boys,” ”Prodigal Sons” and ”Art Stars” frequently stem from already-established positions of inheritance. In other words: privilege does not predicate prodigy. It’s good fun to take a peak behind the curtain: where do worthwhile ideas originate, who is doing the work, who is speaking, who is heard, who (or what) is shunned?

Often portraying rosy-cheeked, seemingly innocent children reminiscent of Hummel figurines which grew in popularity post-World War II in Germany and Switzerland (oddly enough, these same collector’s items have been farcically highlighted or referred to as Satanic, indicators of Aryan or European imperialism and middle-class, consumerist malaise), Saldert’s work uses unbridled potentiality as a thematic forerunner. One example illustrating a vibrant set of youths is Saldert’s The Politics of the Unpolitical, 2011. Ironically, their pastel glow is positioned against the scratchy background of an annihilated cityscape and solitary, leafless tree. Remaining architectural frames resembling apartment complexes in the background are in shambles, hinting at a post-apocalyptic aftermath. The sky appears to be filled with ash or other precipitates.

Are these two soft sprites future lovers? Do they share a platonic camaraderie accessible only to them? What do they mutually regard, and should one read into the fact that no authority figure accompanies their exploration? They appear playful, liberated—like almost everyone either openly or secretly desires to be. Their combined energies, perhaps, serve to override a previous disaster, together scheming to unleash an imagined future.

The phrase the politics of the unpolitical connotes both personal responsibility and the absence of such. When is any thought or action unpolitical? The decision to not act is still a decision—everything and everyone is fundamentally political. One person’s decision to not act affects another individual’s decision to act affects a territory’s ability to progress affects a child born affects a vision uncharted. Not even art escapes such forces of causation and influence. Russian writer Vladimir Nabokov was obsessed with butterflies and a committed taxonomist; he loved the delicate creature’s detail and symmetry. Consider American mathematician Edward Lorenz’s butterfly effect, where one flapping wing inspires the air to tremor causing a gale of wind which becomes a tornado which destroys a house and everyone in it except one entity who survives to become a catalyst for a revolution, or in contrast: a nominal, traumatized offshoot. Underestimating any seemingly insignificant action (or non-action) seems unwise.

To see the review in context, click here.