|

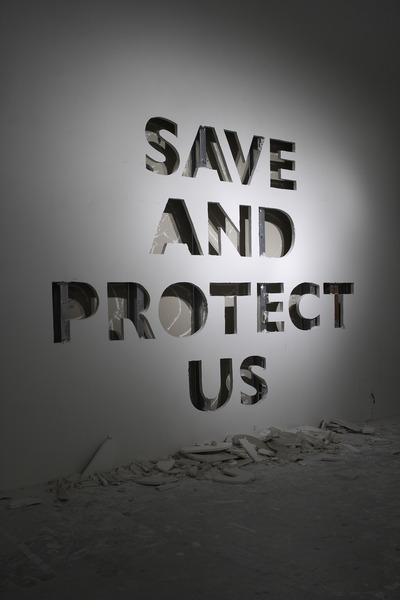

| Petr Davydtchenko, Save and Protect Us, 2011, image: Petr Davydtchenko |

Stockholm, Sept., 2011: For the past three years, Petr Davydtchenko has worked mostly with scenographic installation and sculpture. Davydtchenko prefers to use different media to create dimensions where the border between reality and fiction is blurred. He often sees his work as visually heavy, complete and sometimes even over-burdened by meaning. Combining symbolism, occult and subcultural references with minimalistic expression—this is the way of his practice. The artist attempts to develop new visual codes and reanimate old perceptions of ”good versus evil,” transforming them into something new. Davydtchenko appears to be fully involved in his work, sometimes even using himself as the object of focus. I first encountered his work at student-oriented spaces in Stockholm such as Galleri Konstfack and Showkonstfack, and again recently in Gävle konstcentrum’s “If the Light Should Take Us/Om Ljuset Tar Oss” group exhibition. Davydtchenko is an artist who is not only learning how to play with fire but persuades his viewers to learn how to rub their own two sticks together, to make their own personal flame, to make their own mark.

Jacquelyn Davis: You’re not originally “from” Stockholm. You moved here from St. Petersburg, Russia. When did you make this move and why?

Petr Davydtchenko: Yes, I was born and grew up in Russia. I moved to Stockholm about ten years ago. During my adolescence, my mother, uncle and I often came here to visit friends. My mother moved to Stockholm when I was thirteen—two years later, I graduated from evening art school in St. Petersburg and moved too. I always felt that I wanted to live in Europe, and I really liked Sweden from the very first visit.

JD: Can you explain your relationship to these countries, Sweden and Russia? Do these places respectively influence your practice? Does one place hold more weight than the other?

PD: This relation is complicated. In the beginning, I felt torn away from home, friends and family. I felt that I didn’t belong in Sweden and even wanted to move back to St. Petersburg. When years passed, I was able to gather more experience and understanding of both countries, but at the same time, I didn’t feel at home in either of them. Somehow, I am standing in the middle. My Russian background is a main source of my inspiration/my core, but it was during my stay in Sweden that I was able to develop my views on contemporary art and society.

JD: Art in the Public Realm, as both an artistic method and socio-political strategy, is a growing trend among many artists in Stockholm—and elsewhere. How does your own artistic practice relate or play into this public art-making approach?

PD: I work a lot with interactive installations/projects that usually invite the viewer into a direct collaboration. Most of the time, I work with site-specificity, and a space in-and-of-itself plays an important role in my practice. Although, I am not sure if I am working in this particular field, where borders seem diffused at the moment. The definition seems too abstract, but the idea is interesting.

JD: You and I both had academic stints at one of Stockholm’s art and design schools: Konstfack. Now that you are no longer a Konstfack student, what conclusions have you reached about your arts education and the role that this institution had in your creative development?

PD: When I applied to Konstfack, I knew that it would be a challenging education, that I would have to find my place in this institution without losing my values. It is always important for me to be able to keep my work flow and at the same time: to be able to integrate into the academic system. After three years at Konstfack, I feel grateful for the challenges and experiences that I gathered. Konstfack played a huge role in my artistic development, but more importantly the people with whom I worked with back-to-back during these years.

JD: When examining your art, I’m curious about whether or not you have strong political or religious leanings. If so, do these ideologies serve as motivation for the way in which you express yourself?

PD: I come from an orthodox background. During my youth, church and religion played a huge role in Russian society. Actually, it still does. When in Russia, I often visit some of Saint Petersburg’s most amazing churches. The atmosphere there is very powerful, and it is hard to not feel the sublimity present. The regime in Russia definitely left its mark on my vision of political systems. Corruption and power abuse are a part of everyday life there. Religion and politics definitely are fodder for my practice. Both admiring and questioning religion and the State in my work helps me investigate myself and society.

JD: What do you expect from Stockholm’s artistic community? Are you satisfied with the city’s creative scene and opportunities? What do you think is missing from Stockholm’s community?

PD: I definitely hope for improvement in Stockholm’s art scene. The gallery scene is uptight. It seems that there is a certain form/style of art that has its place there, and it is hard to find something different—something that sticks out. I wish that Stockholm’s art scene would be more open and daring. During these last two years, there definitely was improvement, but it has a long way to go. I just hope that the upcoming generation of artists will be able to make a change. More collaborations with young artists from other countries, more pop-up non-commercial galleries willing to exhibit different types of projects. I hope that the scene gets looser so people can be more relaxed with themselves and able to give way to more spontaneous creativity.

JD: How have you evolved into the artist that you are now? Was it spontaneous or gradual? A conscious decision or a particular feeling or idea which consumed you or took control? I’m curious about the idea of the artist as an active instigator vs. the artist as a more passive mechanism of some perceived fate or inherited responsibility.

PD: I have been involved in the art scene since I was born. Both of my parents are artists. During my youth, I spent a lot of time in the studios of artists in St. Petersburg. Actually, my mother was still in the art academy when I was born. Sometimes, she took me to seminars and even to her examination. I wasn’t thinking so much about whether or not to become an artist until I got into pre-art school on the west coast of Sweden. During my second year there, I realized that I really wanted to be an artist. It was there that I made a conscious decision to work towards becoming an artist. During that year, I also chose to apply to Konstfack.

JD: Where do your ideas come from? Is there a distinct pattern or generalized method for your inspiration?

PD: My inspiration usually comes from a certain place or an event that I can relate to mentally or spiritually. I often gain inspiration by exposing myself to places that have an, often, uncanny or mysterious energy. Most of my works are in that way site-specific. Although, when I find myself using a certain method for several projects, I usually try to change it. It is comfortable to use a common pattern for creating a piece, but in a way, it can also limit your output. By breaking and recreating different patterns, I try to evolve and—at the same time—remain passionate about my work.

JD: You state that you want to create new visual codes and revive the concept of “good versus evil”— that it is important for you to be fully engrossed in your art, being, sometimes, even the object of your work. The division between the artist and artist’s work is complicated—where one sphere ends and another begins. What have you gained by being the object of your art? Examples of this are present in Gävle Konstcentrum’s “Om Ljuset Tar Oss/If the Light Should Take Us” exhibition: your video work Run Paint Run, Run, 2010 and image The Hanged Man, 2010.

PD: I am fascinated by the Fluxus Movement from the 60’s. The artists of Fluxus Movement saw that every action of their daily life could be an act of art-making. I do not want to separate myself from my art—instead: to be one with it, at least during the process of making. Performance is a tool in my practice. By making actions that are usually documented and shown as video material in the exhibition space, I try to show my own impressions through physical actions of self punishment and rituals. Run Paint Run, Run is a video where I am moving through the winter landscape of the forest. I have ink poured all over me, and I am dragging a metal sign that says MAYHEM. I continue walking until I fall on the ground and then crawl with the sign, leaving traces of black ink on the snow. This video is an allegory of self-punishment combined with a visualization of one’s own darkness coming out in the form of black liquid. Both Run Paint Run, Run and The Hanged Man were made during a period were I was struggling with fear and darkness inside of me. In a way, it was a method of self-therapy and even a religious act of purification.

JD: The “Om Ljuset Tar Oss/If the Light Should Take Us” exhibition received mixed reviews and slight controversy due the fact that it drew attention to ideas revolving around black metal, pagan ideologies and related iconography. I’m interested in hearing more regarding your perspective as to why you incorporate such symbolism into your art—what is your motivation? Do you feel that this exhibition was a success, despite controversy?

PD: Yes, definitely. I think that this exhibition was a success. The fact that it awoke a debate around Nazism and Right-Wing extremism is quite interesting and important for modern society. These questions have a direct relevance to what is going on in almost every country. My negative experience from the Neo-Nazi Movement in Russia played a huge role in the themes that I chose to work with. When I moved to Sweden, the Black Metal Movement caught my attention because I found similarities between it and the Neo-Nazi Movement in St. Petersburg, Moscow and other cities in Russia. By working with these themes, I try to continue the discussion around evil in society and individuals. At the same time, I’m investigating my own stand on the matter.

JD: Though this question may be viewed as personal, it’s sometimes hard for me to differentiate between appropriate versus inappropriate inquiries of public and private. What do you find to be most sacred, valuable and important? And do any of these convictions bleed into your art? Can you give an example?

PD: For me the most sacred thing is to stay “human.” I admit that I have a certain fascination with darkness. Works that were presented in the exhibition “Om Ljuset Tar Oss/If the Light Should Take Us” are interpretations of dark events and thoughts which bother me. When shown to public, they stand for themselves and are separate from me. Although these works are very personal, they are open for interpretation by me and the viewer.

JD: Other works such as Save and Protect Us, 2011 and your jewelry piece which reads MAYHEM incorporate text into your practice. How much do other texts or text-based works of other artists or writers serve as fodder for inspiration? Are you drawn to the texts of certain artists or writers—whether classical or contemporary? If so, who and/or what specific text-based works?

PD: I am fascinated by words and often use them directly as objects. Text is used in my work in different forms. Sometimes, it is a base, and it is only I who knows where the source comes from. For example, my inspiration for Exploring The Fire was Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury: a dystopian novel about exploring humanity’s flaws, the government’s desire to control humanity and the constant struggle of individuals to break from chains. In Fahrenheit 451, we are taken to a future where a fireman’s job is to start fires to burn books rather than put fires out. While based on a horrific future, metaphorically, the book can be taken as a direct comment on modern society and the way in which we conform without really questioning or trying to extend our boundaries. MAYHEM jewelery is a piece based on a logo of a Norwegian Black Metal band. In this work, I am trying to disconnect it from its origin and present it as an object that can be read and interpreted by viewers who may have no knowledge of this Scandinavian subculture. I find the work of artists like: Matias Faldbacken, Banks Violette and Andrei Molodkin interesting and similar to my own. They all use words and text in their practice in very direct and powerful ways.

JD: If you were given the opportunity to erase, destroy or remove an aspect of yourself: your history, previous creations, a success or failure … which would somehow improve you as an artist, what would you choose to erase or destroy? I suppose it could also be a ’who,’ if need be.

PD: At the moment I do not have any need for such an opportunity. Of course, I’ve made mistakes and regret some things that I’ve done in life, but they have also led me to where and who I am now. If I didn’t make any mistakes and didn’t go though some uncanny experiences, I am sure that some of my best works would not exist.

JD: Do you think that art possesses any real ability to save lives?

PD: I’ve met people in my life who were broken down and have lost their passion for living. Some of them later became involved in art making and found a new spark. On a bigger scale, I do believe that art plays some role in this matter, but it is not a direct one.

JD: Do you have plans to collaborate with certain artists or writers in the future? I enjoy seeing artists in Scandinavia actively working with those in both their immediate area and abroad. What are your sentiments towards experimental collaboration? Do you think that they work?

PD: Yes, definitely! It may have amazing results. I also enjoy seeing this way of collaboration in Scandinavia and abroad. Such collaborations can open up new dimensions for both sides. I have positive experiences of working with other artists, architects, designers and musicians and thinking of expanding collaborations into other fields. At the moment, I am planning a collaboration within the field of neural science, but it is too early to live out details.

JD: Your works such as Trespassing Without Interfering, 2009, Tower of Burned Paintings, 2009 and Exploring the Fire, 2010 are architectural—even sculptural. The two are not always disparate. You introduce specific spatial symbolisms: house as a domestic sphere; tower as power, escape and fantasy; barn denoting attention to the rural milieu. Yet, you often destroy these symbols or re-appropriate them to suit your intentions. Why are you using these architectural icons—what do you wish to relay? What do these architectural symbols mean to you?

PD: Representation of buildings, especially houses, is a large part of my practice. For me, a house can stand for many things, but the most important is the idea of the house as a person. The house as a body representing an interpretation of a human being. With the facade as a face and the inside with its history, secrets, darkrooms and basement, I see an architectural construction as a perfect form which can be used in projects that touch both society and the individual.

JD: Do you consider yourself to be a site-specific artist? Do you think that you would you be producing the art that you make now if you were situated elsewhere—not in Scandinavia?

PD: Yes. As I mentioned earlier, I often gather my inspiration from a certain place. The theme in my work often depends on where I am living and working. When I feel that it is important for me to work with a particular matter, I try to go there and gather impressions and do field studies. Scandinavia and Russia hugely influence the art that I make. I do not think that my work would look the way it does if I didn’t spend my time in these places.

JD: What are your future plans? Do you think that these plans will impact your art? How?

PD: I have just moved to London to start my M.A. in the Sculpture Department at RCA. I think that living and working here will help me find new sources of inspiration and develop my work on this particular site. The atmosphere here is Raw and Gothic. There are many beautiful cathedrals and mysterious places. Also: the way that social structures appear here—it makes my hands scratch to start working with projects. The dream is to create a community within several countries. I hope to continue collaborations with people from Sweden and Russia—not only by making projects but also creating events and shows together on a larger, international scale.To see the interview in context, click here.